Three meals a day, 365 days a year, Mom delivered. The planning, the prep, the presentation, all of it in high heels and pearls. What she did in the kitchen every day was tangible proof of her love.

Cooking was expected of moms back then, especially in the South. No shortcuts, at least not in my mom’s circle. The discovery of one TV dinner carton in the trash was enough to warrant immediate expulsion from bridge club, followed by a public electrocution.

Mom never cooked to keep up. She led the pack. Because of her, I remember my childhood in forkfuls. The tens of thousands of meals she made in that kitchen — still makes in that kitchen — are among my favorite memories of home.Except for three:

Liver. No matter how it’s prepared, liver always ends up tasting like what it is: a bovine internal organ designed to rid toxins from the blood of cows. Responsible moms were forced to serve it back then. Something about the iron. My mother was never able to explain this in a way I understood, so I grew up thinking that if I didn’t eat liver I’d never learn to iron. Which explains the way my shirts look today.

Spinach Swirls. They weren’t swirls, they were balls. Green globs of spinach, chopped, mixed with some binding agent (liver?) and pressed into spheres the size of plums. When Mom proudly set them before us on a plate, my brother Jimmy immediately pointed out that they looked like the round clumps of grass a lawnmower spits out when you mow it wet. Mom froze. But it was George, five at the time, who really nailed it: Spinach Swirls were dead ringers for those little green horse turds. “Wow, they look exactly like the BMs horses drop in the summer!” George was banished from the table. But so were the Spinach Swirls. Never served again.

Chicken Elizabeth. This is a dish so infamous in my family that the mention of it at a family gathering is guaranteed to turn my mother to stone. So we bring it up often. Mom found the recipe for something called “Chicken Elizabeth” in one of her women’s magazines. So sure was she that this would turn out to be her crowning culinary creation that she saved it for Mother’s Day.

What made Chicken Elizabeth such an extravagance was that the recipe called for chicken breasts only, unheard of at the time. Ten huge breasts, sautéed in butter and baked to perfection under a chunky sauce of onions, celery, blue cheese, sour cream and vermouth. My mother’s devotion to perfecting it was so single-minded that she didn’t even go to church that day. Mom only skipped church when giving birth. But both of my grandmothers were visiting from out of town, and was determined to blow them away.

When Mom triumphantly set her silver-platter masterpiece down in front of her mother-in-law, we were all blown away. But not in the way Mom intended. And while none of us ever got to taste her jewel, Norman Rockwell missed out on the Mother’s Day magazine cover of his career: my grandmother choking, then vomiting all over the Chicken Elizabeth. Also, never served again.

But these were the exceptions. Most days Mom killed it in the kitchen. I assumed all moms did.

It was only after I started spending the night at other houses that I began to learn the truth. There were lazy moms, and they cheated. Taking in the landscape of their kitchens — boxed mac-and-cheese, Hamburger Helper, frozen pizza, TV dinners, takeout burgers and pizza — how was I to know I was looking into a crystal ball and seeing my own future?

It’s true. Destiny fated me to become one of the lazy moms. When I left home for college, I had no idea I’d never eat so well again. But it wasn’t until I had mouths of my own to feed that I realized cooking isn’t genetic.

The argument could be made that Chicken Elizabeth Sunday scarred me. How else to explain the fact that despite the excellent model of my mother, I’m a washout in the kitchen? Entire days have gone by when I’ve not realized until five in the afternoon, “I forgot to feed the kids.”

It’s not that I can’t cook. I do a great Thanksgiving dinner. It’s an exact duplicate of my mother’s. The first time I prepared it for friends in New York, she had to talk me through the entire meal as I was cooking it. Over the phone. From South Carolina. The long-distance cost more than the food. My dad had cereal for Thanksgiving that year.

I also make excellent birthday cakes. From scratch. Kelly and the kids each have a signature cake I create just for them every birthday. Delicious. So I’m capable. But a sprinter. Able to deliver on selected holidays, but hibernating when it comes to feeding my family the other 361 days of the year.

For this reason I’ve always avoided the Food Network. Who needs the shaming? All those spiffy chefs in their pressed aprons and glossy kitchens make me want to puke all over a Chicken Elizabeth. They make cooking look easy. Cooking is not easy. Bobby Flay never dropped an open bag of flour, staggered through a gluten cloud and crashed into his refrigerator.

My daughter loves the Food Network, can watch it for hours. I never understood why until I realized that for Elizabeth it’s aspirational. It’s her way of pretending there’s actually food in the house.

Which brings us to Daphne Dishes, my favorite new television show. How, you ask? I will tell you.

Last fall I was contacted by my son’s 4th grade room parent to see if I’d lend a hand chaperoning 66 fourth graders on a field trip to the San Juan Capistrano Mission. I have the utmost respect for room parents. Room parent is a job so deadly it would make the leader of ISIS choose immolation. It’s thankless, constant and brutal. It makes all the other parents feel less than while simultaneously thanking Jesus it’s not them.

Since our kids were in kindergarten, Daphne Brogdon has volunteered for this task almost every year. So when Vivien’s mom asked if I’d help chaperone these kids to the mission, how could I say no? My only stipulation: Could chaperones maybe skip the bus and drive the two hours each way together in a separate car?

It was on this car ride to San Juan Capistrano that Daphne casually mentioned — as casually as if she were repeating the weather forecast — that she’d just been offered her own show the Food Network. I don’t know where you live, but even in Los Angeles there’s never been a room mom who got her own show on the Food Network.

Despite my rocky relationship with the Shame Network, I promised Daphne that James and I would tune in to watch her debut show. It was the least I could do to repay all the times she’d punctured herself stapling together parent contact sheets and washing glitter and glue out of her hair.

In the entertainment industry, tuning in to someone’s first episode is what’s known as a “courtesy watch.”

It turned out to be an intervention. A kitchen intervention. Like most interventions, everyone knew I needed it reckoning desperately, except me.

In days my family was feasting on real food, cooked by me, food that didn’t start life surrounded by cardboard.Right away I loved the title: Daphne Dishes. It was easy, breezy and fun, like Daphne.

But I almost turned off that first episode after hearing the theme — “Mom’s Gone Healthy.” Too many triggers. But I stuck with it because it was Daphne.

I’ve always liked Daphne. There’s nothing phony about her. She doesn’t mind looking as crappy as you at 8 a.m. Zero problem showing up at drop-off with her hair flying, no makeup, wearing a shirt with eggs on it. She’s also the mom who, on a 2-hour drive to a mission, makes sure to point out every single David Beckham underwear billboard. That’s a mom I like.

On that first episode, James and I watched as Vivien’s mom explained in terms any fool could understand every step of what she was doing and why. I was immediately comfortable because I’ve been in that kitchen before — it’s not a set; they film at her house. The nooks and crannies were known to me: I remember where the jelly’s stuck to the side of the refrigerator from last September because I slipped there! That’s where I tried to chug the dregs from a bag of Cheetos and clogged Daphne’s pasta maker! That’s the sofa cushion where I hid James’ nine cookies, sat on them, then forgot about it!

Daphne on TV turned out to be the same Daphne I knew from school, only with makeup and hair because the network insists. Daphne’s funny on her show. She spills things. I could totally see her staggering through a gluten cloud.

For that first show Daphne made a Pecan-Stuffed Chicken Breast, Blistered Tomatoes and Feta Cheese along with something she called Crowd-Pleasing Couscous. She topped it all off with a little treat called Dark Chocolate Sauce Over Fresh Berries. Which turned out to be dark chocolate sauce over fresh berries. I love that.

The big surprise was that Daphne made me believe I could do this too. The next day I took a list of all the ingredients and that night I tried to re-create the entire meal from “Mom’s Gone Healthy.” It went amazingly well. The only hard part was skewering the chicken breast. But I’ve never been good with a skewer and string.

After Daphne’s first few dishes, I began to hear sounds at the table I’d never heard before.

Like Mmmmmm.

And that’s when James something he’d never uttered in nine years:“Daddy, this is the best meal you’ve ever cooked! Can you make this every night?”

And I did. Until after the fifth time the crowd-pleasing couscous was no longer pleasing the crowd. But that was okay, because by then it was time for Daphne’s second show, “Comfort for a Friend.” (Pan-Roasted Chicken with a Creamy Mustard Sauce, Horseradish Mashed Potatoes, Crispy Brussels Sprouts and something called Cafe Bengali. I had no idea what Cafe Bengali was, but it didn’t matter. At this point I was hooked).

I was at the store the following morning armed with my shopping list. “Comfort for a Friend” became my family’s new favorite meal. And it went on like that for seven weeks. New week, new meal. My husband, my children were saying things that brought tears to my eyes, things like:

“Daddy can cook!”

“I know. How dope is that?”

It was almost like magic. I felt as if I’d somehow managed to pull a twenty-foot scarf out of a turkey’s butt.

June 4, 2015

Share this column or post comments below.

I had spotted him months before at one of our school’s Friday-morning sings. Ruggedly handsome, a dark, silent, solid type, he bore a striking resemblance to the Marlboro Man. Beyond noting his resemblance to a cigarette ad, however, I had no feelings about him one way or another. Okay, maybe a couple. Until the night Kelly and I found ourselves at his and his wife’s home for a school fundraising event. I had just finished admiring their kitchen re-model and art collection, when I stepped into their back yard and saw it: The Thing.

I had spotted him months before at one of our school’s Friday-morning sings. Ruggedly handsome, a dark, silent, solid type, he bore a striking resemblance to the Marlboro Man. Beyond noting his resemblance to a cigarette ad, however, I had no feelings about him one way or another. Okay, maybe a couple. Until the night Kelly and I found ourselves at his and his wife’s home for a school fundraising event. I had just finished admiring their kitchen re-model and art collection, when I stepped into their back yard and saw it: The Thing.

Because there’s no way of knowing how much time we have left together, I treasure what my parents have to tell me now more than ever. For the past six years I’ve flown east to spend my birthday week with them, my husband Kelly’s generous gift to us all at the end of every October.

Because there’s no way of knowing how much time we have left together, I treasure what my parents have to tell me now more than ever. For the past six years I’ve flown east to spend my birthday week with them, my husband Kelly’s generous gift to us all at the end of every October.

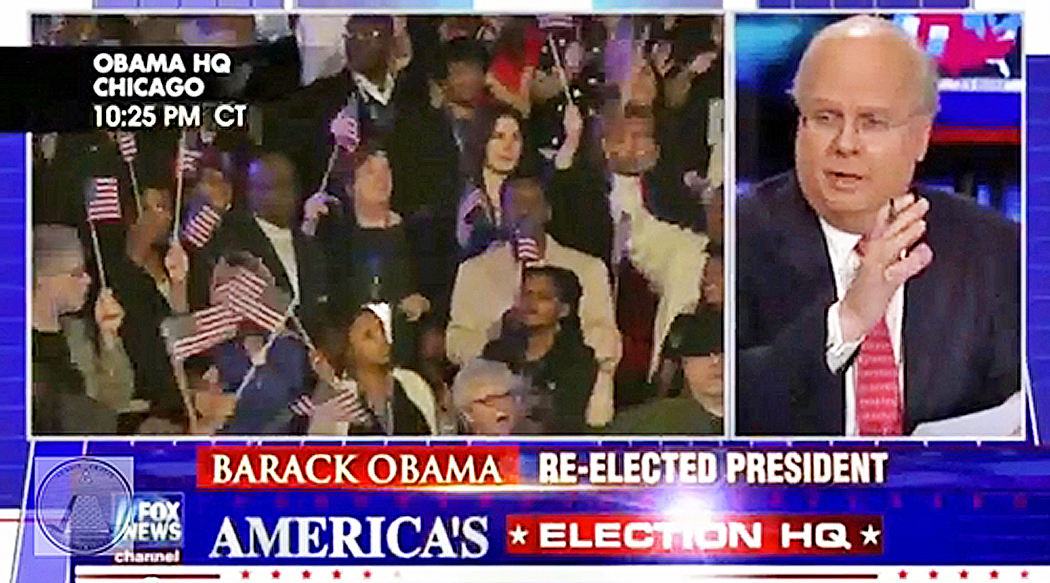

Here’s a fun one to explain to your kids. Thanks, Karl!

Here’s a fun one to explain to your kids. Thanks, Karl!