I’m on the phone with my mom.

“Bill, there’s a hurricane heading straight for South Carolina!”

“I heard.”

“Can’t they do something about that?”

“Mom, who is they? God?”

“I don’t know. Somebody.”

I try but I can’t help myself. I start to laugh. She fails to see the humor.

“Why are you laughing? There is nothing funny about a hurricane heading right at you.”

We call these Betty-isms, my brothers and I. The non sequitur questions and dead-hilarious, off-the-wall observations on the world around her that spill from our mother’s mouth like cultured, absurdist pearls.

They have nothing to do with getting older. Our mother’s been exploding these happy firecrackers since we were children. A sitcom showrunner once told me I bagged a job on his series just by quoting my mother in the interview.

Because there’s no way of knowing how much time we have left together, I treasure what my parents have to tell me now more than ever. For the past six years I’ve flown east to spend my birthday week with them, my husband Kelly’s generous gift to us all at the end of every October.

Because there’s no way of knowing how much time we have left together, I treasure what my parents have to tell me now more than ever. For the past six years I’ve flown east to spend my birthday week with them, my husband Kelly’s generous gift to us all at the end of every October.

When I announced my first birthday-return my mother’s reaction did not disappoint: “What happened? Kelly and the kids don’t want you in California for your birthday anymore?”

At 91 and 93 my parents are — as my dad says — in their gloaming. Gloaming derives from an Old English word referring to those final moments of the day after sunset, as the light begins to fade from the sky, just before the dark sets in. It’s an honest, beautiful, brutal metaphor typical of my father.

While cooking supper for my parents in my childhood home last week, I overheard this exchange as they were watching the news in our den:

“James.”

“Yes, Betty.”

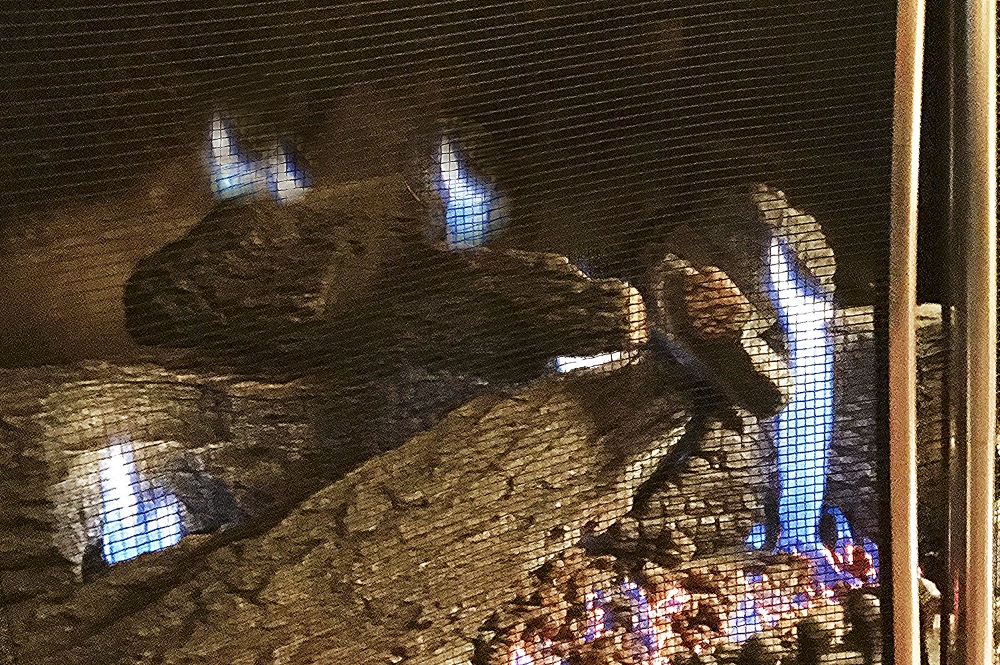

“There’s a dog in the fireplace.”

“Betty, there is no dog in our fireplace. Those are concrete logs.”

“Well, I know it’s not an actual dog. But the logs are shaped just like a little black Scottie terrier. Come look.”

“Why would I want to watch a Scottie terrier getting burned alive in our fireplace?”

I had no idea where this was heading. It could easily have escalated into a protracted, five-minute argument, but instead they both began to laugh at the absurdity of it all, and so did I.

In trying to describe my parents and their 68-year, uniquely charged marriage, I find it helpful to invoke movie characters. My father is Atticus Finch in To Kill A Mockingbird while my mother is Mary Tyler Moore in Ordinary People, as played by Lucille Ball.

Early in my relationship with Kelly, before he’d met Mom and Dad, I used this movie shorthand to describe them. Kelly scoffed at the idea of anyone comparing a living person to the legendary icon Atticus Finch.

Until I brought him home to meet my parents. It was the first time I’d ever brought a boyfriend back to South Carolina, but I’d never felt about anyone the way I felt about Kelly. It was a very big deal. A bigger deal, I soon discovered, to my father than to me. I was surprised when he suggested that instead of staying at their house we book a room at a motel near the highway.

He saw the disappointment in my face and pulled me aside to explain himself. “Bill, this is a small Southern town.” As he spoke I could see his fear was real. Fear not for himself, but for us. There were still laws on the books in South Carolina. Laws he feared the wrong law-enforcement officer might be all too eager to enforce by making an example of his son, knocking on the door in the night to arrest Kelly and me in my childhood home.

The year was 2000, and he knew it could happen. I’d grown up there. I knew it too. But I told him if it we couldn’t stay at his house, we’d fly home. We stayed. When we left on Sunday afternoon, my father gave Kelly a long embrace in our carport and said, “I feel like I’ve met my fifth son.” It was all I could do not to fall apart.

We didn’t talk for the first few minutes as we headed out of town. Kelly spoke first. “You were right. He is Atticus Finch.”

But I’d known that all my life. Before I read the novel To Kill A Mockingbird, I’d seen the film on television. The scene where eight-year-old Scout rides out with her father Atticus to visit Tom Robinson’s house in the “colored” section of town was a total deja vu moment for me. My own father, though not an attorney like Atticus, served a similar small-town population as a small-town family doctor.

When I was a small child, Dad often let me ride along with him when he made house calls at night. I remember sitting on a crate in a house very much like Tom Robinson’s, as black kids my age stared at me, the only white boy who’d ever set foot in their house, with only a lightbulb above us to light our questioning faces. Our trips also took me inside a few of the “richest” houses in town. In those houses, I’d sit on a velvet sofa, marveling at the crystal chandelier overhead.

On our rides home, my father tried to answer the questions that came pouring out of me, about race and money and fairness. I didn’t understand all of his answers, but my questions were his gift to me. Questions I never would have known to ask had he not allowed me to see what he saw every day, the full scope of our town’s humanity.

As we pulled into our own driveway, he said to me for the first time, as he would say many times again in the future: “If you remember nothing else I ever say to you, I hope you’ll remember what my father told me before he died: You are no better than anyone else in this world, and no one is better than you.”

As he did with house calls, my father often took me with him on Election Day, explaining to me that the right to vote, and the responsibility to vote, was one of our greatest freedoms. I remember those mornings, some adults I recognized, a lot I didn’t, and the quiet, serious feeling I always got watching them stand in line, then disappear behind the curtain of the voting booth. When it was our turn, Dad would pull back the curtains and let me look inside at the levers, but when it came time for him to cast his vote, I had to remain outside, so he could be “alone with his thoughts” before he cast his ballot.

Again, on the way home I’d pepper him with questions, mostly on the order of “Can I have one of those booths for my room?” When I became older and asked him to explain the political parties, it was way too confusing. I do remember him saying that in the South most of his white patients probably voted Republican, while most of his black patients probably voted Democrat. When I asked why, he tried to simplify it for me: “Because most of the white people want things to stay the same as they are now, and most of the black people want them to change.”

I asked if that meant he was Republican. He told me he’d never registered as a Republican or a Democrat. He said he tried to read and listen to all the arguments. He told me some people will say anything to get elected. In the end, he said, you look for someone who you believe has morals and integrity and beliefs similar to yours and vote your conscience, because voting is a sacred act.

Even before I was old enough to vote, I realized that I was the political outlier in our family. My parents and most of their friends voted, as they put it, “conservatively.” When I asked my dad what that meant, he said that a lot of people wanted change, but change happening too fast was usually not good for our country. That’s why he was voting for Richard Nixon.

In Nixon’s second term, as the mounting, daily revelations of the Watergate scandal unfolded publicly on the front page of the Washington Post, my parents refused to believe that the man they’d voted for was capable of the “high crimes and misdemeanors” of which he was accused. Kids my age were sure he’d done it. Until the day he resigned in disgrace, my father had believed his lies. He was the President. Presidents don’t lie.

Nixon has come up more than once over the last two years in political conversations with my dad. Once his lies were exposed, all it took to shame him out of office was the backbone of the Republican party and an electorate that didn’t care for lies turning its back on him.

I couldn’t vote yet, but I was starting to pay attention. My mother had no idea that under her roof she was growing a liberal. She blames California. When she told me the only reason I think recycling is normal is because I’ve lived in Los Angeles too long, I started to laugh and said, “Mom, come on, you’ve got to stop acting like there’s something wrong with California.”

“Well, of course there is. That’s why people go there.”

The truth is, my core beliefs about decency and integrity, my sense of what’s right and what’s wrong didn’t sprout on the Left Coast. They took root and bloomed in a segregated Southern town, on those house calls with my father. Riding home in the dark, my father never talked politics, he talked people.

Because of their advanced age and its betrayal of their bodies, my parents spend a lot of time in their chairs these days, tethered to TV and its 24-hour-news cycle. When I’m home, my dad likes to change things up. He’ll switch from CNN to Fox News to MSNBC to golf. Then we play a guessing game about which America we’re really living in.

While I was home I went for lunch with an old friend. As a child I’d always valued her innate kindness and refusal to tolerate racial discrimination in a town that had plenty to go around.

So I was surprised when she told me she was really happy that this administration was “shaking things up in Washington” and “draining the swamp.” Then she paused and shuddered a little before saying, “I just wish he’d stop tweeting. I hate those tweets. They’re so ugly. Why does he have to do that?”

And all I could say was, “Because that’s who he is?”

While I was home news began to break about pipe bombs sent through the mail, addressed to 13 political enemies of the current administration. On Facebook, I wondered if whoever sent them had spent time at a few of those “lock her up” political rallies.

Almost immediately I was pounced on by a guy I went to high school with. He opened by saying that the fact that I lived in L.A. with my “partner” meant everybody knew I had my “wires crossed” in my brain. He went on to mock me for buying into this “libtard plot” about Trump supporters being behind the bombs. He let me know that over on Fox News they had the real story, that it would soon be revealed that the bombs were really sent by Democrats, anxious to take the focus of real threat to America, that dangerous migrant caravan full of Middle Eastern terrorists, the ones “assaulting our country,” all those moms with strollers we’re ready to mow down at the border.

I was figuring out how to address this when a friend posted breaking this news: “7 dead in a synagogue in Pittsburgh today.”

When I got back to my parents’ house, my father just shook his head as the death toll climbed, to 8, then 10, then 11.

News was also breaking that the gunman who’d bypassed white shoppers to open fire on a black woman and man at a Kroger’s market, only did so after failing to break into the black church next door with his loaded weapons.

The perpetrators of all three crimes were quickly arrested. The truth should have surprised no one. Investigation of the three unrelated crimes revealed there was a connection. Again, not surprising. All three acts were acts of terrorism carried out by rabid acolytes of the current occupant of the White House.

The assault on our country isn’t coming from a caravan. It’s coming from within, fueled by distrust, blind hatred and dog whistles. We’re eating each other alive, and the whistle-blower is thrilled.

It’s been years since Nixon shook my father’s faith in the presidency. The last two years, he’s been watching the White House and having flashbacks to his own childhood, a 10-year-old boy watching from shores that had always felt safe, while across the ocean a fascist rose to power, threatening to spread white supremacy and hate not only throughout Europe but around the globe. “He very nearly succeeded,” says my dad, “until decent people stood up to his lies and stopped him.”

Staring into the fireplace, my mom pipes up from her chair. “James, I know you keep saying it’s concrete logs. But I see a dog in flames.”

Vote.

If you’re on the fence, watch To Kill A Mockingbird. It may not change your decision, but it might remind you who you are.

November 4, 2018

Share this column or post comments below.

Excellent, just excellent

You are an amazing writer. I’m going to have to share this story everything you said is right on point. Thank you so much for writing this and pointing out the fact that voting is so important. I am so glad that I can call you my friend.

And I’m happy to call you mine. I was just in touch with your mother, and I’m hoping to have lunch with her in Columbia or Newberry after Thanksgiving. Hopefully you can join.

Jim Winett posted on FB your post. WOW! I didn’t realize how this would go — I don’t want to write too much, but being someone who grew up without parents, your sweet, funny, lovely description of your lovely parents is beautiful. I imagine that’s how it would be for me — the other parts of this post — the chilling realizations and the stern encouragement to VOTE, was not what I expected, but loved that much more! Nice to find you and follow you. Happy evening.

What beautiful words, Carmen. Thank you for reaching out. I got lucky in the parent department, and I’m grateful every day.

So glad that Spilled Milk is back. Thank you for a perfectly timed piece. It’s words like these that remind me that the whole country is not insane, although it has felt like it far too often the past two years. Trusting that Tuesday’s vote will begin to shift things back to normal.

Thrilled that you’re back sharing your life a little. Always “edu-tainting” like Mr Rogers!!

It’s 6am. I’m sick. I just read Spilled Milk. I love it and I love you. You have the talent and the beauty to take the reader in with you. I always feel I’m on your shoulder, laughing, tearing up or just nodding quietly in admiration. And, as always, can’t WAIT for the next installment.

Although I’m not American, I have been listening to what’s going on there. I hope this vote brings the change you need.

Love the stories you share about your own life, your parents, your family. So glad you are back!!!!! xoxo

Bill, I laughed, cried, and loved every thoughtful word. Dad-gum, you sure can write! Thank you for reviving Spilled Milk.

Bill, is that a dog I see in the picture of the fireplace??!!?? Enjoyed reading this. I was not a regular at your dad’s office. We were Blalock/Stephens customers. I guess they were on our side of the tracks 🙂 Your dad has always called me by name and has always been friendly and kind when we crossed paths in the community – your mom equally as kind. I did have the opportunity to visit your dad when I needed to see a doctor while at PC – other side of the tracks then 🙂 Plus, PC would pay for our doctor visits and your dad and Dr. MacDonald were the PC docs. Your story of going with your dad on house calls reminded me of a time, not sure how old we were, I came to your house to play after school. I remember the kindness of your mom and dad most of all. Hope all are doing well.

Gary